|

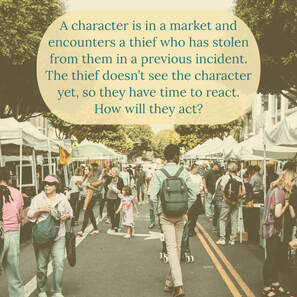

I adapted this blog series from a section of an online workshop I conducted for Writers & Books in March 2020. The SituationDeciding a character’s alignment helps determine how they act during their adventures. I find it helpful to think about how each alignment would behave in the same circumstances because it highlights the differences between each alignment. Here’s the scene: A character is in a market and encounters a thief who has stolen from them in a previous incident. The thief doesn’t see the character yet, so they have time to react. How will they act? A chaotic evil character will viciously pursue the thief with little regard for the safety of the rest of the public in the market–like throwing a grenade at your garden to uproot a weed. There’s also a chance she will ignore the thief, her reaction will depend on how badly she wants the stolen item back and her feelings toward the thief. If she sees the thief as a kindred spirit, she may invite him to join in on her anarchy. Defining Chaotic Evil Characters Loss of life and destruction of property mean nothing to the chaotic evil character. This disregard for any form of social contract usually springs from one of two poisoned wells: vendetta or insanity. Often time, the chaotic evil character is both–a psychotic bent on vengeance. Sometimes, a chaotic evil character has an obsession, and their actions all serve to further their infatuation. Having an obsession is not enough though to make her chaotic evil, though; there’s always an element of derangement in these characters. Chaotic evil characters are rarely antagonists unless the story is a character study, and they are never heroes. Chaotic evil character types include terrorists, mad scientists, psychos, and sociopaths. Chaotic Evil Character Development A chaotic evil character will get more evil or more chaotic. If she tends toward chaos, her behavior will get increasingly erratic as she descends into homicidal mania. While these characters can do an impressive amount of damage in a short amount of time, they either burn out or are apprehended because of their sloppy methods and lack of planning. On the other hand, the character might become more evil. Instead of merely being chaotic, she could learn to sew the seeds of mass chaos through scheming and underhanded dealings. While her personality will still be unstable, she’ll be able to see her nefarious plots through to the end. Chaotic Evil Character Examples  Iago from Shakespeare’s Othello is the “sewing the seeds of chaos” character type. He’s a master manipulator who harnesses the power of chaos to reach his goal. Iago doesn’t have the instability often seen with chaotic evil characters, aside from when he alters his personality to suit his needs. The Joker from the Batman franchise is the standard chaotic evil character who is wildly insane and bent on revenge. In many of his stories, the Joker becomes more villainous, starting out as petty and then moving on to enact more complex crimes. Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, is one of those rare chaotic evil characters who you might feel some sympathy for. Judge Turpin drove him to madness, and his reason for seeking vengeance is understandable. But, he kills people and eats them, so our understanding can only go so far. Next week I’m discussing neutral good characters! Other Blogs in This Series:

4 Comments

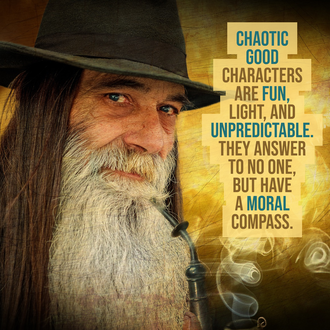

This blog series is adapted from a section of an online workshop I conducted for Writers & Books in March 2020. The SituationDeciding a character’s alignment helps determine how they act during their adventures. I find it helpful to think about how each alignment would behave in the same circumstances because it highlights the differences between each alignment. Here’s the scene: A character is in a market and encounters a thief who has stolen from them in a previous incident. The thief doesn’t see the character yet, so they have time to react. How will they act? A chaotic neutral character is likely to ignore the thief altogether in favor of his own mad schemes. The fact that the thief stole something from him is low on his list of concerns unless the thief stole something precious to him or someone he loves. Then, he’ll pursue the thief in any number of erratic ways. He might chase him, attack him, throw something at him, or even silently stalk the thief home to ambush them. Or, maybe he’ll befriend the thief. It’s all on the table. Defining Chaotic Neutral Characters Chaotic neutral characters are the most unpredictable of all the alignments, and they are singular in their ability to cause mayhem. They are, however, not emotionless slaves to chaos. On the contrary, chaotic neutral characters are driven by strong emotions and the need to act on those feelings When a chaotic neutral character feels a sudden burst of joy, he acts on it. Maybe he expresses his joy by giving out flowers to passersby or by baking a copious amount of bread. When a chaotic neutral character feels jealousy, he acts on it as well. However, he’s just as likely to harm the subject of his envy as he is to befriend her. He may even ignore her in favor of improving himself until he’s no longer jealous. At times, he may cycle through emotions, and related actions, quickly, handing out flowers one moment and kicking a lady he’s jealous of the next. Chaotic neutral characters tend to be pirates, pranksters, and vigilantes. They are often exiled to the fringes of society due to their lack of desire, or ability, to control their emotions and actions, unless they live in a lawless or chaotic civilization. Chaotic Neutral Character Development A chaotic neutral character’s actions are not necessarily neutral, but his good actions and his evil actions cancel each other out, resulting in a net neutral. He’ll steal from the homeless encampment today and feed the homeless encampment tomorrow. Extending the length of his moods is one way to develop a chaotic neutral character. He can move from being able to focus on a task for only a few minutes to staying on track for hours, then days. His actions will still be erratic, and he may be prone to outburst, but he’ll be able to set a goal and reach it, even if his goal only makes sense to himself. Chaotic neutral characters may be devoted to someone or something. Though the character’s devotion rarely extends to a structured organization, he may have a love interest, or be dedicated to a loose ideology, such as hedonism or anarchy. His life journey may revolve around winning his love or becoming a master anarchist. In the end, however, the sum of his life will be almost as if he never existed, because a chaotic neutral character habitually nullifies any of his own achievements. Chaotic Neutral Character Examples  Dr. Frank N. Furter from The Rocky Horror Picture Show is an example of a chaotic neutral character devoted to hedonism. He has massive mood swings. He’s kind, manipulative, and selfish, almost simultaneously. He does, however, stay focused on a task and achieve a goal, a skill lacking on many chaotic neutral characters when they begin their adventures. Gollum from Lord of the Rings has no idea what he’s doing. He has no plan and no goal outside of staying close to the ring until he’s able to get it back. Any good he does is quickly undone by his own evil actions. Puck from A Midsummer’s Night Dream is the agent of chaos type of chaotic neutral character. He acts randomly and watches the results of his action as entertainment. He doesn’t mean harm, nor does he mean good. He just asks on his whims whenever they occur to him. “If we shadows have offended, Think but this, and all is mended, That you have but slumber’d here While these visions did appear. And this weak and idle theme, No more yielding but a dream.” – Puck Next week I’ll be discussing Chaotic Evil Characters (shudder)! |

Alison Lyke

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed