|

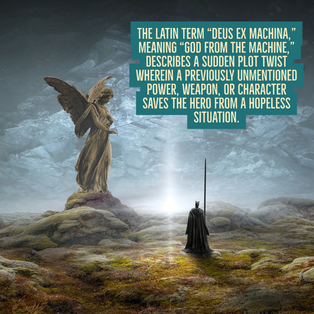

From swashbuckling sword-and-sorcery to motorcycle chases through cyberpunk neon streets, well-written action scenes are an integral part of many sci-fi and fantasy stories. Good combat sequences and action scenes happen fluidly and are part of the story’s flow. Satisfying action scenes are simple to read but not so easy to write. In this series, I’m investigating what goes into a successful action sequence. Bad ActionMost of the time, I don’t think about an action scene unless it’s especially good or terrible. In today’s blog, I will explore some of the trouble spots in action scenes and discuss possible fixes. DisorientationThe problem: Where are the combatants? The inability to discern where the action is happening is one of my biggest pet peeves in action scenes. In these types of scenes, a fight might break out in a bar, then move to an alley, then they break through an alley door into a warehouse, then they’re in a room in the warehouse with explosives for some reason, then they’re in a room with machinery, and on and on. This much movement is jarring, disorienting, and often narratively unnecessary. Even worse are narrative jumps from one space to the next with no explanation. If a pair of swashbucklers duel on a promenade and their swordplay inexplicably moves to the deck of a ship, this takes me out of the story because I need to know how they moved locations. Both issues have the same result. The reader leaves the narrative to figure out where they are. There must be a happy medium between a tedious slog through locations and a sudden jump in the scenery. The fix: If I’m planning on moving my characters through an area at top speed, I might survey the area first. Letting my characters and readers get the lay of the land while everything is calm. This solves both problems of too much movement and location skipping. While my characters enter the bar, I might describe the alley and the adjoining warehouse so that when they’re fighting, they can move through it with a narrative quickness that befits a fight scene. Also, I consider how much the characters need to run for the combat to make sense. Do they really have to travel through half a dozen spaces? I might skip some of the places they’re moving through and focus on where the action happens. Similarly, if I first depict the promenade as a loading dock hosting a great ship, then the swashbucklers moving onto the boat makes sense. Later in this series, I will write a whole blog to discuss orienting action in further detail because there are a ton of unique ways to describe combat movement. Sudden Boosts The Problem: The Latin term “Deus ex Machina,” meaning “god from the machine,” describes a sudden plot twist wherein a previously unmentioned power, weapon, or character saves the hero from a hopeless situation. These sudden boosts can be a fun narrative surprise, but they can also be frustrating for readers when executed poorly. A Deus ex Machina character may suddenly shoot fireballs from their hands during a combat scene. Other examples include someone who has been hiding a gun all along and pulls it out just in time to kill an advancing zombie or a situation where a long-lost sorcerer father who swoops in to save the protagonist. These abrupt additions to the story might make readers think the author is writing themselves out of a corner. The fix: Hints and foreshadowing are the solutions to the Deus ex Machina dilemma. Maybe once or twice during the story, the character has a fire start around them when sleeping, or a candle lights when they’re reaching for it. That way, it makes sense when their hands suddenly shoot fireballs during intense combat. Readers don’t need to guess what’s going to happen, but what does happen needs to make sense in retrospect. Negligible Wounds“It’s just a flesh wound!” – Monty Python and the Holy Grail The Problem: If a character gets, say, stabbed in the leg, their movement should be impeded by the leg wound until it heals. Barring healing magic, if a character suffers mortal injuries, they should die (or almost die). Someone who loses an eye can’t see as well. Someone who had a gash across their cheek has a scar there. You get the picture. The fix: This is an easy one. Give the character impediments appropriate to their injury. Remember to describe their healing as well. On the other hand, don’t go crazy with constant descriptions of pain. I once read a book where the main character suffered a concussion, and every third sentence described his headache. This went on for three chapters. It got to the point where I’d just laugh out loud every time his head pain was mentioned again. Bad action scenes don’t necessarily ruin a story, but it does bring the reader out of the story and can wreck narrative immersion at critical moments. For the rest of the series, I’m focusing on how to build literary action sequences that bring your story to life.

0 Comments

|

Alison Lyke

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed