|

Well-written action scenes are integral to many sci-fi and fantasy stories, from swashbuckling sword-and-sorcery to motorcycle chases through cyberpunk neon streets. Good combat sequences and action scenes happen fluidly and are part of the story's flow. Satisfying action scenes are simple to read but not so easy to write. In this series, I'm investigating what goes into a successful action sequence. I’m going to split the topic of magical combat into two subsets: supernatural and sorcery/wizardry. Also, are the Jedi from star wars using supernatural magic, or are they sorcerers? I don’t know. You’re going to have to yell louder; I can’t hear you. Supernatural Combat Supernatural is sort of a misnomer here because magic in this category comes “naturally” to the practitioner as part of their physiology. Vampires, fairies, and ghosts all fall into this category. As well as any creature or person who can innately perform magic. This is an important distinction, supernatural creatures don’t have to learn their magic, but they are not necessarily good at it. This means that young or newly magical creatures will not have as good control of their magical abilities. On the other hand, you don’t want to meet a thousand-year-old vampire in a dark alley. Supernatural creatures from lore (fairies, werewolves, etc.) have predetermined powers and limitations to guide combat. No one is bound by the rules of legends, but they can be a helpful guide. Sorcerous Combat Combat spells are fun to write. They are a chance for limitless creativity because anything is possible in the realm of magic. On the other hand, to guide the narratives, magicians often have a specialty. A magician may specialize in learned spells (often called wizardry) or potions. Different magical groups include: healing, natural (including the four elements or specializing in an element, i.e., pyromancy), necromancy, and psionics (mental powers). There’s also a personal favorite of mine, chaos magic, wherein the characters must contend with unpredictable results. By virtue of their innate abilities, a supernatural character may often be a specialist in one of the above areas. Although, an interesting character may want to work in magic that goes against their physiology. I’d read a story about a fairy-turned-necromancer. Selecting a magical specialty has a few advantages. Inexperienced characters may move up the ladder of their abilities with increasingly impressive displays of magic. A pyromancer may begin with little, uncontrolled fireballs and work up to targeted missiles of fiery destruction. Staging Magical CombatThe previously mentioned D20 Method for writing combat can also work for magical action, with spells or magical effects doing the damage instead of weapons. If you use this, you’ll either have to use magic from D&D books (there’s a ton) or come up with your own statistics for spell damage. Whether or not you use the D20 system, you’ll need to figure out the damage, duration, and lethality of magic effects. For example, if a psionic blast knocks the victim unconscious, how long does it last? Or, how deadly is a wound from a spirit blade, and so on. Also, mixing exciting regular combat with magical combat can make for an epic battle. Next UpSpeaking of epic battles, I had a lot of fun writing this blog series. It took forever to get through it because I was in the middle of a challenging time in my personal life. But, as always, this blog and your comments and participation is a wonderful little bright spot. This fall (which is in a few weeks already! what?) I’m starting a new blog series on writing villains. I can’t wait to do a deep dive into bad guys! Other Blogs in this Series:

0 Comments

Well-written action scenes are an integral part of many sci-fi and fantasy stories, from swashbuckling sword-and-sorcery to motorcycle chases through cyberpunk neon streets. Good combat sequences and action scenes happen fluidly and are part of the story's flow. Satisfying action scenes are simple to read but not so easy to write. In this series, I'm investigating what goes into a successful action sequence. Weapons as Window Weapons can be used as a window into the fantasy or sci-fi world. In the post-apocalypse, maybe all the weapons are hundreds of years old and must be maintained by specialists. Perhaps, in your fantasy world, the only weapons are wands, the crafting of which is an esoteric art. At the very least, your weapons should match your world, and if they don't, there needs to be an explanation as to why. Fantasy Weapons and Armor '"Mithril! All folk desired it. It could be beaten like copper, and polished like glass; and the Dwarves could make of it a metal, light and yet harder than tempered steel. Its beauty was like to that of common silver, but the beauty of Mithril did not tarnish or grow dim." – Gandalf in The Fellowship of the Ring I highly recommend using reading up on historical weapons, especially for a fantasy setting. You'll want to know the difference between a shortsword and a broadsword or a crossbow and a longbow. Not everybody has to wield a sword, either. Whips are extremely handy in combat, for example, and there are a bunch of different kinds. Similarly, there are all sorts of armors that have varying degrees of permeability and maneuverability. Some armors are so hard to get on and off that the character will need aid when dressing for battle. Considerations like these are what make the special touches that help your readers feel immersed in your world or, at the very least, suspend their disbelief. Of course, in some fantasy settings, the primary weapon is magic. I’ll be covering magical combat in the last blog in this series. Weapons with magical effects need to be considered as well in any fantasy setting, from sword-and-sorcery to urban fantasy and everything in between (I’m looking at you steam-punk). Figure out the rules that guide your magic weapons and armor and follow them, even if you don’t spell them out to the reader. Sci-fi Weapons and Armor Similar to magical weapons, weapons of the future have rules. Still, unlike their fantasy counterparts, sci-fi weapons must follow the laws of physics and, unless we’re talking alien tech or far future, they have a developmental lineage. This is good news because it gives a blueprint for futuristic weapons and a frame of reference for readers. A nerve-paralysis gun, for example, is a weapon I just made up (although it’s probably not novel). It shoots out nanobots that temporarily paralyze the victim. The linage of the weapon is still there, even though it’s nearly unrecognizable. The user points and shoots like a gun. Maybe it has a safety and a trigger. The futuristic elements of the nerve-paralysis gun tell us a little about the world it came from as well. We now know about the nanobots and, once you know about them, there’s no going back. “Never let the future disturb you. You will meet it, if you have to, with the same weapons of reason which today arm you against the present.” ― Marcus Aurelius Quest Weapons Often in fantasy and sometimes in sci-fi, procuring a special or superpowered weapon is a significant plot point. Perhaps your characters are searching for a sacred sword lost to history. Maybe, they have to wrest a mighty scepter from an evil sorcerer. Whatever the quest, it’s essential to handle the physical acquisition of the weapon properly. Often, the story ends when the main character secures the quest weapon or shortly after. This makes it, so the writer doesn’t have to deal with the issues that arise when your character suddenly becomes superpowered by wielding her new weapon. If the story doesn’t end, then the author has to figure out some way to curb the weapon's power. This could include the need to destroy the weapon for the good of the world, a curse upon the weapon wielder, or a limited number of uses. Building epic weapons, figuring out characteristics, and coming with lore can be a fun way to add to your world. The features could be anything usually achievable by magic or potion, including poison, flame, luck, healing, sure strike, and so on. Tying the weapon’s power to the world’s history can be an incredibly revealing narrative element. Other Blogs in this Series:

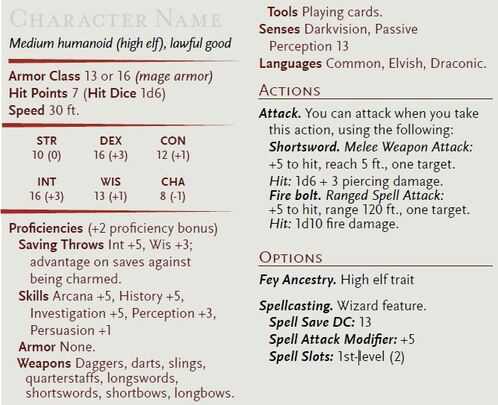

From swashbuckling sword-and-sorcery to motorcycle chases through cyberpunk neon streets, well-written action scenes are an integral part of many sci-fi and fantasy stories. Good combat sequences and action scenes happen fluidly and are part of the story's flow. Satisfying action scenes are simple to read but not so easy to write. In this series, I'm investigating what goes into a successful action sequence. I'm a lifelong Dungeons and Dragons player, and I use many D&D techniques when writing (see my entire series on using alignment to write characters). Even if you're not a D&D player, you can still use a 20-sided die (D20) to aid in writing combat scenes. Using die rolls adds an element of chance to action sequences, making them easier to write and more realistic. Character StatisticsIf you're familiar with D&D, you might want to just write up a whole character sheet for each of your main characters and, maybe, a less detailed one for any other characters involved in combat. Character sheets are a great way to create a "sketch" of your characters, even if you're not going to use them for battle. You can find a collection of blank and prefilled character sheets here: https://dnd.wizards.com/charactersheets As you can see from the sheet, you give numbers to your character's attributes. A lot of these, such as charisma and wisdom, are primarily for character development. But, many of them are useful for combat and action scenes. Attribute ranking for most characters will range between one and five. Five, however, should be used only if the character is very proficient or even a master in the category. A negative score indicates an area of weakness. Character statistics are added (or subtracted) from die rolls, then it's up to me to decide what those die rolls mean. Rolling Combat As the author, I know how I want the scene to turn out. I know who is going to win and who is going to wound. Rolling for combat adds an element of guided chaos to my action scenes. Here's an example of how I might use the D&D technique to create an action scene: I have two characters: Robin the fairy and a troll name Rax. Robin is small, so she has stats that give her a roll modifier of -1 in strength, a +3 in dexterity, and she has 8 hit points (hit points are the number of points of damage she can take before she goes unconscious or dies). Rex has +2 strength, -1 dexterity, and 12 hit points. Robin has a dagger that does 1d3 (one three-sided die roll) of damage, and Rex has a sword that does 1d6 of damage. For simplicity, let's say that both characters are not wearing armor, which makes their armor class 10 plus their dexterity modifier. So, Robin has an effective armor of 13, and Rex has 9. These are the numbers the other character must overcome to make physical contact.

Already we see that the size and skills of the two fantasy characters are represented with the numbers. There's a whole system for deciding who goes first in combat, but we're going to skip that today too. We'll assume that Robin goes first because her high dexterity means she's generally faster. Here are the rolls and how I interpret them for combat: Round 1: Robin Rolls 19(-1) total: 18 Rex's Armor: 9 I think: This is more than enough to make contact and is a lucky strike for Robin. I roll a d3 and determine that she makes 3 points of damage. If I want, I can even use a body die to roll where Robin hit Rex. What I write: Rex watches for a moment as the little fairy comes barreling down the trail, her wings furiously beating as they carried her along at top speed. Is she really going to try to attack me? Rex lazily looks down at his scabbard, wondering if it was worth it to draw the sword or if he could just swat her away. In the millisecond he wasn't looking, Robin flew to his side and jabbed her deadly sharp dagger into his ear. "Bugger," Rex yelled as he unsheathed his sword and clasped his hand to his bloody ear. Round 2: Rex Rolls: 7 (+2) total: 9 Robin's Armor: 9 I think: Rex's hit doesn't overcome her armor class, but it almost does. It's not a great roll, and I need to reflect that in the story. What I write: Still grasping his ear with one hand, Rex swings wildly with his sword. His sword is so big, and Robin is so tiny, he almost crushed her with the broadside. Robin flitted away, searching for her another chance for a swift attack. … and do on… I might also watch the number of hit points left to determine when a character is wounded or killed, or I might use my own judgment. Usually, it's a mix of both. Quick Roll I don't have to write out a whole character sheet to determine the outcome of a combat situation or action scene. For quick encounters, side characters, and short stories, I might just quickly roll a 20 sided (or any-sided) die to see who wins an encounter and by how much. In these cases, it's more of a writing prompt or a way to keep the words flowing without having to stop typing for long. If I already have a character sheet made, that makes die rolls even quicker and backloads with more information. Die rolls can also determine the outcome or act as prompts for magic duels or attempts at magic and non-combat situations like trying to persuade or trick a character. Other blogs in this series:From swashbuckling sword-and-sorcery to motorcycle chases through cyberpunk neon streets, well-written action scenes are an integral part of many sci-fi and fantasy stories. Good combat sequences and action scenes happen fluidly and are part of the story’s flow. Satisfying action scenes are simple to read but not so easy to write. In this series, I’m investigating what goes into a successful action sequence. Baked-In Skills The narrative’s time and place are the first things I consider when writing an action scene. I’m going to talk about character ability soon, but the story’s circumstances can sometimes dictate a character’s skills, so it’s an important consideration. There may be a particular set of physical or societal conditions that give all characters a base physical skill set. For example, members of a post-apocalyptic society where everyone fights for resources will have a different skill set than a group of elf nobles from a high-fantasy novel. Characters from the post-apocalyptic might all be able to sprint while carrying heavy loads. That skill may come into play in an action scene, and the “winner” of the combat would need more than those base skills. Character Ability Next, I consider the character’s physical abilities and if they’ve had any specific training. I use my prewritten character profile for the main characters. If I’m writing about an ancillary character, I might need to write up a quick character sketch to flesh out the combatant. When I write out this brief background, I focus on her combat skills and how she got them. Combat Styles A character’s combat style is often about skills they have gained from training. This is what makes the combat or action sequence interesting. Maybe they are skilled at swordplay or at martial arts. Perhaps they fight with laser guns or with magic missiles. The setting you create during your worldbuilding will also affect your character’s ability to gain these skills. A world where most contact is digital may not have much hand-to-hand combat, and there aren’t many firearms in sword-and-sorcery settings. However, none of these rules are hard and fast. But, if your sorcerer has a gun, you better be able to explain why (see my entry on Deus ex Machina). Other Blogs in this Series:

From swashbuckling sword-and-sorcery to motorcycle chases through cyberpunk neon streets, well-written action scenes are an integral part of many sci-fi and fantasy stories. Good combat sequences and action scenes happen fluidly and are part of the story’s flow. Satisfying action scenes are simple to read but not so easy to write. In this series, I’m investigating what goes into a successful action sequence. Bad ActionMost of the time, I don’t think about an action scene unless it’s especially good or terrible. In today’s blog, I will explore some of the trouble spots in action scenes and discuss possible fixes. DisorientationThe problem: Where are the combatants? The inability to discern where the action is happening is one of my biggest pet peeves in action scenes. In these types of scenes, a fight might break out in a bar, then move to an alley, then they break through an alley door into a warehouse, then they’re in a room in the warehouse with explosives for some reason, then they’re in a room with machinery, and on and on. This much movement is jarring, disorienting, and often narratively unnecessary. Even worse are narrative jumps from one space to the next with no explanation. If a pair of swashbucklers duel on a promenade and their swordplay inexplicably moves to the deck of a ship, this takes me out of the story because I need to know how they moved locations. Both issues have the same result. The reader leaves the narrative to figure out where they are. There must be a happy medium between a tedious slog through locations and a sudden jump in the scenery. The fix: If I’m planning on moving my characters through an area at top speed, I might survey the area first. Letting my characters and readers get the lay of the land while everything is calm. This solves both problems of too much movement and location skipping. While my characters enter the bar, I might describe the alley and the adjoining warehouse so that when they’re fighting, they can move through it with a narrative quickness that befits a fight scene. Also, I consider how much the characters need to run for the combat to make sense. Do they really have to travel through half a dozen spaces? I might skip some of the places they’re moving through and focus on where the action happens. Similarly, if I first depict the promenade as a loading dock hosting a great ship, then the swashbucklers moving onto the boat makes sense. Later in this series, I will write a whole blog to discuss orienting action in further detail because there are a ton of unique ways to describe combat movement. Sudden Boosts The Problem: The Latin term “Deus ex Machina,” meaning “god from the machine,” describes a sudden plot twist wherein a previously unmentioned power, weapon, or character saves the hero from a hopeless situation. These sudden boosts can be a fun narrative surprise, but they can also be frustrating for readers when executed poorly. A Deus ex Machina character may suddenly shoot fireballs from their hands during a combat scene. Other examples include someone who has been hiding a gun all along and pulls it out just in time to kill an advancing zombie or a situation where a long-lost sorcerer father who swoops in to save the protagonist. These abrupt additions to the story might make readers think the author is writing themselves out of a corner. The fix: Hints and foreshadowing are the solutions to the Deus ex Machina dilemma. Maybe once or twice during the story, the character has a fire start around them when sleeping, or a candle lights when they’re reaching for it. That way, it makes sense when their hands suddenly shoot fireballs during intense combat. Readers don’t need to guess what’s going to happen, but what does happen needs to make sense in retrospect. Negligible Wounds“It’s just a flesh wound!” – Monty Python and the Holy Grail The Problem: If a character gets, say, stabbed in the leg, their movement should be impeded by the leg wound until it heals. Barring healing magic, if a character suffers mortal injuries, they should die (or almost die). Someone who loses an eye can’t see as well. Someone who had a gash across their cheek has a scar there. You get the picture. The fix: This is an easy one. Give the character impediments appropriate to their injury. Remember to describe their healing as well. On the other hand, don’t go crazy with constant descriptions of pain. I once read a book where the main character suffered a concussion, and every third sentence described his headache. This went on for three chapters. It got to the point where I’d just laugh out loud every time his head pain was mentioned again. Bad action scenes don’t necessarily ruin a story, but it does bring the reader out of the story and can wreck narrative immersion at critical moments. For the rest of the series, I’m focusing on how to build literary action sequences that bring your story to life.

|

Alison Lyke

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed