|

A story can have a vibrant world and a brilliant plot, but it’s all for naught if the characters don’t act like genuine people (or elves, trolls, whatever, you get it). This blog series is about creating authentic characters who act and react realistically in fantastic and futuristic worlds. Elements of Dialogue Patterns Authentic characters have actions they’d never take, but they also have words they’d never say. A lot goes into your character’s dialogue, but most important is their education level and upbringing. A character’s intelligence and how well-read they are doesn’t influence their alignment or motivation unless they are motivated by gaining wisdom. Still, it does come into play when deciding how a character speaks and what kind of vocabulary they use. Give your character a few favorite words, slight affectations, and grammar patterns. You might want to start by looking over a list of rhetorical devices and assigning a few to some of your characters. Perhaps you have a character who favors the rule of three or is fond of alteration. Other traits can inform dialogue; a shy character will try to speak less than a gregarious one. The goal here is, if you read just the line of dialogue with no other context, would you be able to tell which of your characters said it? Look at this piece of dialogue from The Two Towers by J.R.R. Tolkien. You don’t need the dialogue tag to figure out who said, “Now, Mr. Frodo…” “Why, Sam,” he said, “to hear you somehow makes me as merry as if the story was already written. But you’ve left out one of the chief characters; Samwise the stout hearted. ‘I want to hear more about Sam, dad. Why didn’t they put in more of his talk, dad? That’s what I like, it makes me laugh. And Frodo wouldn’t have got far without Sam, would he, dad?’” "Now, Mr. Frodo," said Sam, "you shouldn't make fun. I was serious.” "So was I," said Frodo, "and so I am. We're going on a bit too fast…" Ye Olde Annoying Dialogue Dialogue patterns and particular words may be specific to the world you've built, so take the overall culture into consideration when crafting speech. I'd caution against attempting to make your dialogue sound "old English" because it's in a high fantasy setting or futuristic because it's a visionary sci-fi. These mannerisms end up making your dialogue unreadable. Very few readers want to wade through "Ye ole" and "thou" to discern what a character means to say. Instead, pepper your dialogue with references to the elements in your medieval or futuristic worlds. Similarly, steer away from characters with stutters, lisps, and heavy affectations or accents, unless their minor characters, the dialogue will be too difficult for your reader to slog through. Unique Voices For this last activity, give your character something to say. Maybe they will introduce themselves to you. Perhaps your character will comment on being dragged into this world by you (kicking and screaming?). Possibly, they have something to say about the outfit you're wearing, or have them discuss this morning's news. Whatever it is, make sure it's in your character's unique voice. That's the last blog in this series, but I already have another one in the works! I hope you enjoyed it!Other Blogs in This Series:

0 Comments

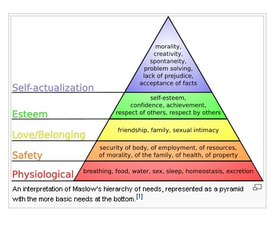

A story can have a vibrant world and a brilliant plot, but it's all for naught if the characters don't act like genuine people (or elves, trolls, whatever, you get it). This blog series is about creating authentic characters who act and react realistically in fantastic and futuristic worlds. Small Pieces of History A character's authenticity, motivation, and alignment came from somewhere. The character's "backstory" is how she became who she is. The length and detail of her character backstory is somewhat subject to her age. For example, a forty-year-old will have more history than an eighteen-year-old, unless maybe the eighteen-year-old has been through a lot and the forty-year-old has had an exceptionally dull life. Backstory writing is tricky because the more detailed it is, the less of it ends up in the story. Reveal too much information about a character and, well, it's no longer her backstory; it's turned into the story. Instead of including all her backstories, have a small piece of character history come up in conversation or reveal a tidbit of her past at the right narrative moment. Formative Events  Even if most of it doesn't end up in your final draft, it's handy to know the formative elements of your character's past to help you understand her motivations and choices as she moves through your world. Consider the other traits you've given her so far and think about how those traits developed. What happened to her that made her chaotic good? Why are they motivated by financial gain? Etc. Formative bits of backstories don't have to come from significant life events, though they often do. Consider this life-altering bit of information delivered by the narrator's grandfather in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451: "Everyone must leave something behind when he dies, my grandfather said. A child or a book or a painting or a house or a wall built or a pair of shoes made. Or a garden planted. Something your hand touched some way so your soul has somewhere to go when you die, and when people look at that tree or that flower you planted, you're there. It doesn't matter what you do, he said, so long as you change something from the way it was before you touched it into something that's like you after you take your hands away. The difference between the man who just cuts lawns and a real gardener is in the touching, he said. The lawn-cutter might just as well not have been there at all; the gardener will be there a lifetime." The character's conversation with his grandfather on the importance of things left behind is a formative part of his history and motivated this character's curiosity and eventual protection of books throughout the story. Writing Backwards To practice your backstory skills, choose a character, and write a piece of their backstory that helped form their personality. For example: Let's say I have a lawful good character raised by a mother in law enforcement. Or a character who is motivated by altruism because they grew up penniless. If these elements end up in your narrative, you can breathe life into them with fascinating details Next week is the last blog in this series and it's all about dialogue!I finished National Novel Writing Month (whew!) and I'm ready to continue this series... A story can have a vibrant world and a brilliant plot, but it's all for naught if the characters don't act like genuine people (or elves, trolls, whatever, you get it). This blog series is about creating authentic characters who act and react realistically in fantastic and futuristic worlds. Real MotivationTo effectively and convincingly move through a fantastic world, characters need a prime motivation. This motivation should be separate from the story's plot and may even run counter to the narrative. For example, a character who wants to be a knight going on a quest to become a knight is supremely dull. Take a character who only wants to become an academic and force her into a knight's journey; Now we're cooking. I'm not saying that the plot should always run counter to a character's motivation, just that motivation needs to be exciting and can be separate from the plot. When a character is inauthentic, it's often because they either don't have any motivation or act in a way that's counter to an established prime goal. A character who is only about gaining esteem will not disrespect a superior without reason. A homeless character who needs shelter won't turn down a free night in an inn just because he doesn't follow the innkeeper's religion. Motivation as a Hierarchy  One way to choose your character's motivation is to place them on Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs chart. In Maslow's needs, motivation moves through five stages, progressively, so once the character fulfills the requirements on one step, their goals move on to the next. These stages include: The physiological need for food, shelter, sex, and similar physical needs makes up the pyramid's bottom. The next set of requirements is safety and then love and belonging. Next on the pyramid is esteem and respect. Finally, spirituality, creativity, and self-actualization drive top-tier motivations. You can see how powerful these motivations can be in driving your character forward and giving them some personal background and context in your world. For example, a character whose primary motivation is to find food is in a different place in life than someone who is looking for love and family, and both are separate from a character who is searching for spiritual meaning. Moving a character's motivation through Maslow's chart can provide character growth throughout the story arc. Maybe your character starts out as a thief who steals for food and shelter, attempting to meet needs at the base of the pyramid. With some newfound powers, the character gets all their physical and safety needs met and now wants to find love and belonging. (I realize I just gave an outline of Disney's Aladdin, but it still works as a story arc). A Note on Obsession Motivations are compelling, but note they're not obsessions, although an obsession can spur a motivation. A character who wants to find a girlfriend differs from a character who is obsessed with a certain woman. Motivation Development When you write a character, give her a primary motivation. Think about where on Maslow's hierarchy she might land. What needs they already take care of, what still should be fulfilled, and where would she like to go next, whether her journey is physical, professional, or spiritual. You can be general with your motivation; for example, maybe your character just really needs to feel safe or to find love. Or perhaps she has a specific motivation to rule a kingdom or undo a wretched curse. Other Blogs in this Series:A story can have a vibrant world and a brilliant plot, but it’s all for naught if the characters don’t act like genuine people (or elves, trolls, whatever, you get it). This blog series is about creating authentic characters who act and react realistically in fantastic and futuristic worlds Crafting CredibilityCharacters in sci-fi and fantasy often have paragon attributes and powers far above the average person walking around on the street. Even an ordinary citizen in a sci-fi likely has sensational gadgets that we don’t currently have access to. So, how do we make an elf, wizard, or bionic woman seem more realistic? The best way to ensure the authenticity of any kind of figure is to craft your character, give them a set of distinguishable traits, and, and this is the most crucial part, stick to those traits. In successful science fiction or fantasy stories, the audience suspends their disbelief. For me, I’m willing to allow a writer to take me on implausible journeys to distance futures and surreal worlds. I want to believe in an alien or wizard. When a wizard or alien acts out of character or does something only to blatantly further the plot, my disbelief returns, and I’m no longer wrapped up in the story. I may even stop reading it. Hobbits Hide and Dragons Hoard  Read this exchange from J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, between the hobbit Bilbo Baggins and the dragon Smaug: "Well, thief! I smell you, and I feel your air. I hear you breathe. Come along! Help yourself again, there is plenty and to spare!" But Bilbo was not quite so unlearned in dragon-lore as all that, and if Smaug hoped to get him to come nearer so easily, he was disappointed. "No thank you, O Smaug the Tremendous!" he replied. "I did not come for presents. I only wished to have a look at you and see if you were truly as great as tales say. I did not believe them." "Do you now?" said the dragon somewhat flattered, even though he did not believe a word of it. "Truly songs and tales fall utterly short of the reality, O Smaug the Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities," replied Bilbo. "You have nice manners for a thief and a liar," said the dragon. Bilbo is tiny and rogue. Lying isn’t beneath him, and hiding is a necessity. Here, the dragon’s natural strengths, his enormous size, and his gold hoard are detrimental because Bilbo is, by nature, adept at hiding. While both characters are tricky, neither of them fools the other. This is important. Bilbo tricking the dragon might help the plot, but you don’t get to be an ancient, wealthy dragon if you’re fooled by the first bit of flattery hurled your way. Bilbo wouldn’t go charging at the dragon to slay him. He’s a hobbit; hobbits hide. To ensure characters’ authenticity, they must have a set of distinctive attributes and a background story that plausibly gives rise to those traits. They should adapt and change throughout the story in an arc that makes sense to their history and personality. The Bilbo Baggins at the end of The Hobbit differs from the one at the end of the book, but he still has most of the same fundamental characteristics. Authenticity in Action To check for authenticity, take a few minutes and write something that your character would never do. Maybe they’d never eat meat, perhaps they’d never have children, perhaps they wouldn’t steal under any circumstances or go to bed without saying their prayers. Next, start building their backstory by writing why they’d never do it. Other Blogs in this Series: A quick note: This will be my last blog for a month, apart from my Tripping the Multiverse cover release on November 17th. I’m taking part in NaNoWriMo for November. I’m only completing half the challenge. I can’t commit to a full novel because *gestures to everything,* but I plan on completing the second half of the next book in my Jade and Antigone series. Exciting times!

A story can have a vibrant world and a brilliant plot, but it’s all for naught if the characters don’t act like genuine people (or elves, trolls, whatever, you get it). This blog series is about creating authentic characters who act and react realistically in fantastic and futuristic worlds. Writing a rough character sketch is the first step to creating a fully formed fantasy or science fiction character ready to adventure in your world. Character sketches should focus mostly on the character’s traits and personality instead of looks. It’s much easier to craft your character’s outside once you’ve figured out their insides. Plus, their physicality might change throughout your personality crafting. Maybe their backstory gives them a scar, or they belong to an order wherein everyone has purple hair. Even though looks come later, you might not want to start from a blank slate, so your character basics might include a rough age, gender, and body type. I also like to add their name, their goals, and some stand out personality traits. Stand out qualities might include friendliness, level of conscientiousness, and emotional stability (or lack of these). Sometimes, I start out with none of these, or just a name, and let the character reveal herself to me as I work through their backstory. But starting with a rough sketch often best. Here’s a checklist to help create character sketches

That’s really it for the sketch list. Keep in mind a character sketch doesn’t have to meet all these criteria and often includes other info, such as the narrative reason you’re creating the character. Next blog, I’m going to discuss a few quick tricks to make even minor characters authentic. Other Blogs in This Series: |

Alison Lyke

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed